Building reliable multi agent AI systems

LLMs are limited to frame their answers within their context window, which can be very limited in some cases. Agents working in loop have massive prompts, conversation history, system instructions, or documents, all lies inside that window leaving a very little space for the next step. This becomes more relevent in agents which works in longer duration. In such senarios a single agent system might run out of context and the quality of the result regrades exponentialy. Here comes the need of multi-agent systems.

A multi-agent architecture distributes the work across agents, each with its own context window. This adds more capacity to work in parallel and gives more token space to think. In effect, it scales token usage for tasks that exceed the limits of a single agent.

Each agent tries to fit all the necessary information and reasoning inside its context window. For complex tasks that need multiple tool calls or handle large information, the context window fills up fast, limiting the final result. A multi-agent architecture distributes the work across agents, each with its own context window. This adds more capacity to work in parallel and gives more token space to think.

In effect, it scales token usage for tasks that exceed the limits of a single agent. Each agent tries to fit all the necessary information and reasoning inside its context window. For complex tasks that need multiple tool calls or handle large information, the context window fills up fast, limiting the final result.

But multi-agent systems have a downside too. They burn through tokens like crazy making them expensive when exposed to tasks which could have been handled by a single agent system. Also, tasks that require all agents to share the same context are not a good fit for parallel execution, because LLM agents are not great at communicating with each other in real time.

Context is everything

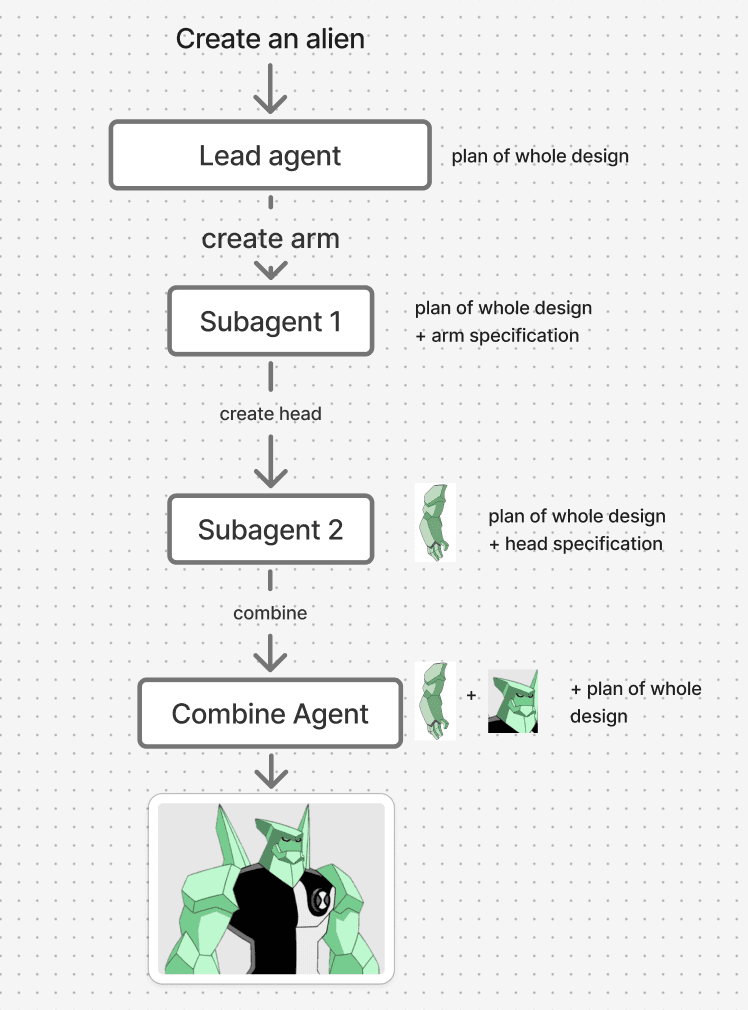

While multiple agents increase capacity, they also make coordination much harder. Each agent only knows what's inside its own context window. If two subagents need similar background information but receive slightly different details, they may make different assumptions. When their outputs are merged, the final result might not align — like assembling a body where each part was built with a different design in mind.

This happens because actions carry hidden decisions, and conflicting decisions create bad results.

To solve this synchronization problem, we must turn to context engineering. Carefully deciding what each agent should know, how much to share, and when to pass it along. Each subagent needs a clear objective (what is it solving?), a defined output format (what shape should the answer take?), tool guidance (what resources can it use?), and boundaries (what is not its job?).

Without this structure, subagents can duplicate work, miss gaps, or pull inconsistent data. A key idea here: don't just share messages; share full agent traces. An agent's reasoning steps, what it tried, what failed, what choices it made, can be as valuable as its final answer when coordinating complex workflows.

Single-threaded linear agent

Let the subagent 1, complete its task and then pass the context and result (or necessary details) to the subagent 2. This will allow the agent 2 to pick up things aligned with the the other agent. This might sound like a workflow, and unfashionanle but this simple architecture will get you very far, but for those who have truly long-duration tasks, and are willing to put in the effort, you can do even better. This can be solved by context engineering. Share only the key moments and decisions to the next agent.

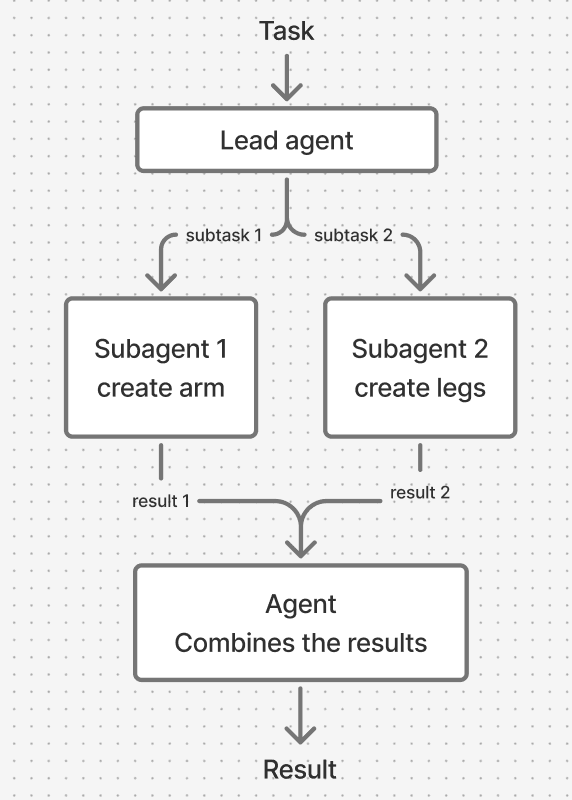

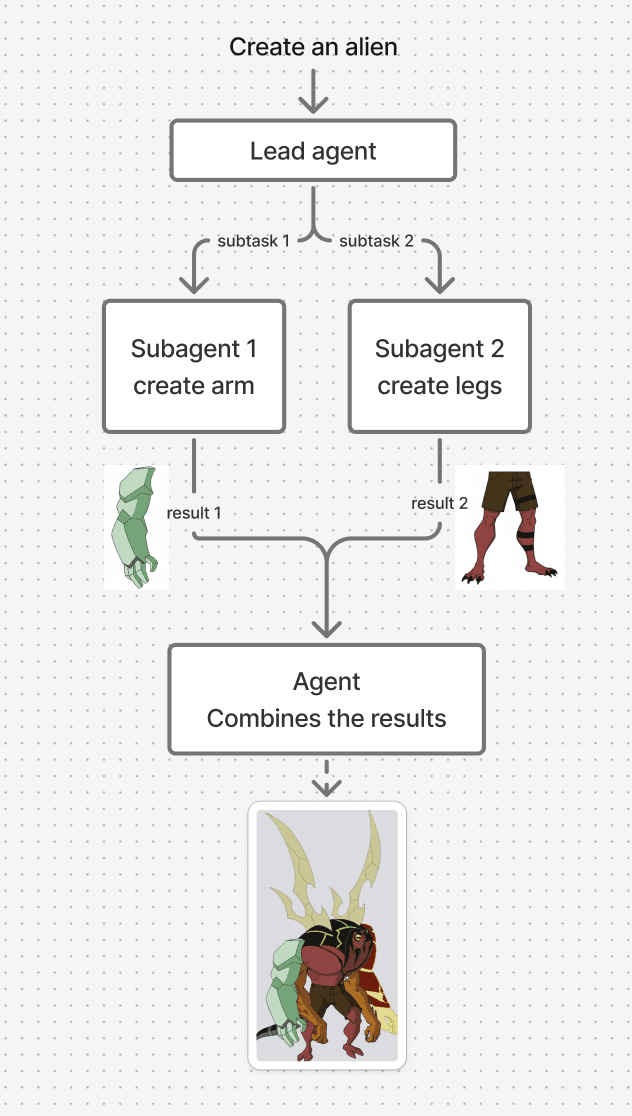

Multi threaded (parallel) agent

Parallel sub-agents are useful when tasks can be divided such that one sub-task needs almost no information from another. Each subagent needs an objective, an output format, guidance on the tools and sources to use, and most important a clear task boundries. Without a detailed task description, agents can end duplicating there efforts performing same tasks. Multi-agent system which can run as many instances of the same subagents as it wants, struggles to judge appropriate number of subagents required for a task. It's important to embed constraints and goals directly into each sub-agent's prompt so they know exactly what to do and when to stop.

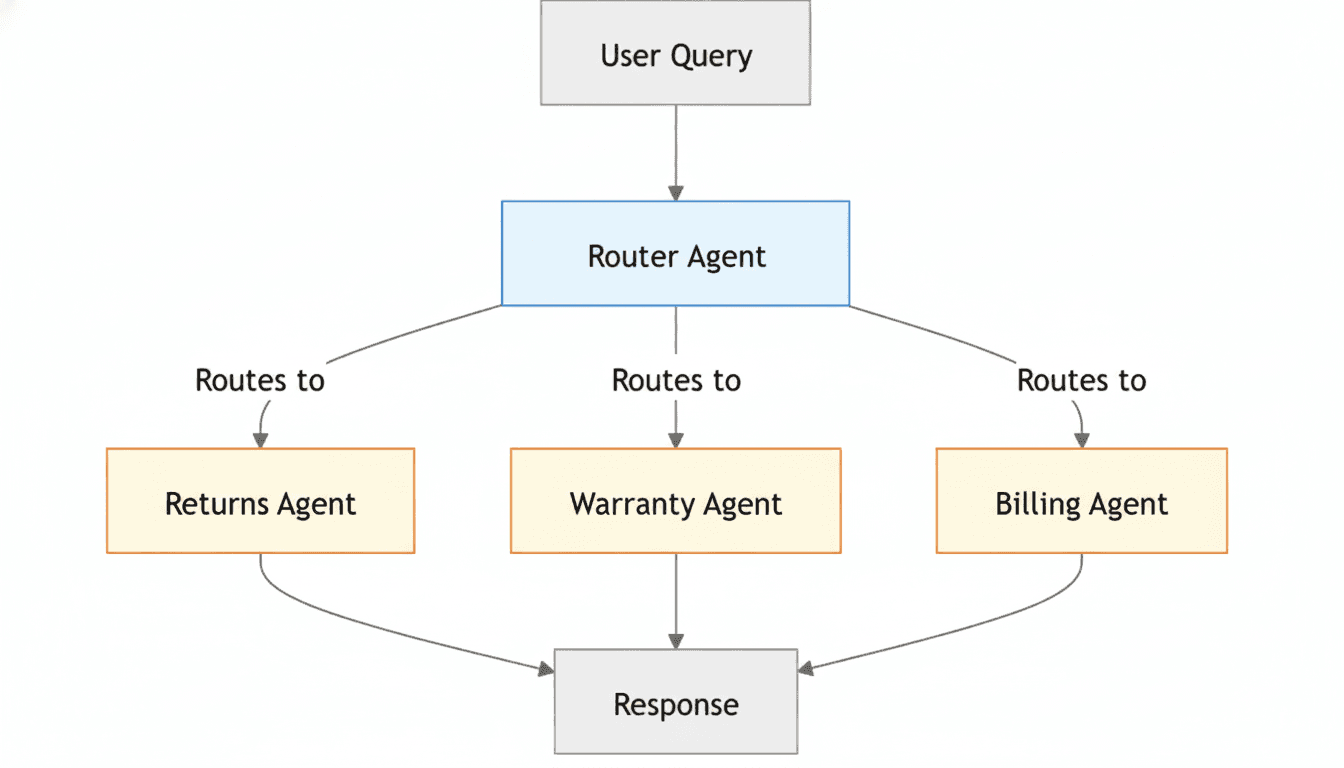

Supervisor (Router) multi-agent systems

The lead agent not ony breaks the objective into subtasks but also acts like a supervisor, routing each subtask to the most appropriate specia subagent. This architecture is widely used in customer facing chatbot like agentic systems.

Another variation of this is where the objective is not broken down into subtasks to be assigned to different agents, but they fails in multi-topic querries. For example, "Hey, I want to check warrenty of my device and also would like to return it.", here if the objective is not broken into "check warrenty" and "return policies" it will be divereted to just a single agent which will leave user with only one answer. While teams at Parlant are researching single-agent routing, I argue that subtasks remain superior because they enforce deterministic boundaries—preventing the 'hallucination drift' common in generalist agents.

Error handling

LLMs are unpredictable at times, and that makes multi-agent systems error-prone. Restarting the whole process after an error is not an option. It's expensive and users hate it. A good system should be able to resume from where it got stuck. To achieve this, store the agent's context in external memory until the job is finished. This allows the agent to recover and continue without losing progress. It's important for the agent to recover by its own from errors. LLM models can be excellent prompt engineers, they can analyse why the failure occured and possible fix for it, suggesting the agent to recover by prompting it.

Conclusion

Building a reliable multi-agent system is less about having many agents and more about how well they talk to each other. Adding more agents increases capacity, but without strong context sharing and clear task definitions, it just creates confusion faster. The real challenge is coordination - giving each agent enough context to do its job while keeping the overall process aligned. Context engineering, structured communication, and self-recovery make multi-agent systems not just powerful, but dependable. At the end of the day, it's not about parallelism for its own sake. It's about building systems that can think together, not just at the same time.